Infinity * 89

Process and pulse through Steve Reich's 89 years

I do not mean the process of composition, but rather pieces of music that are, literally, processes.

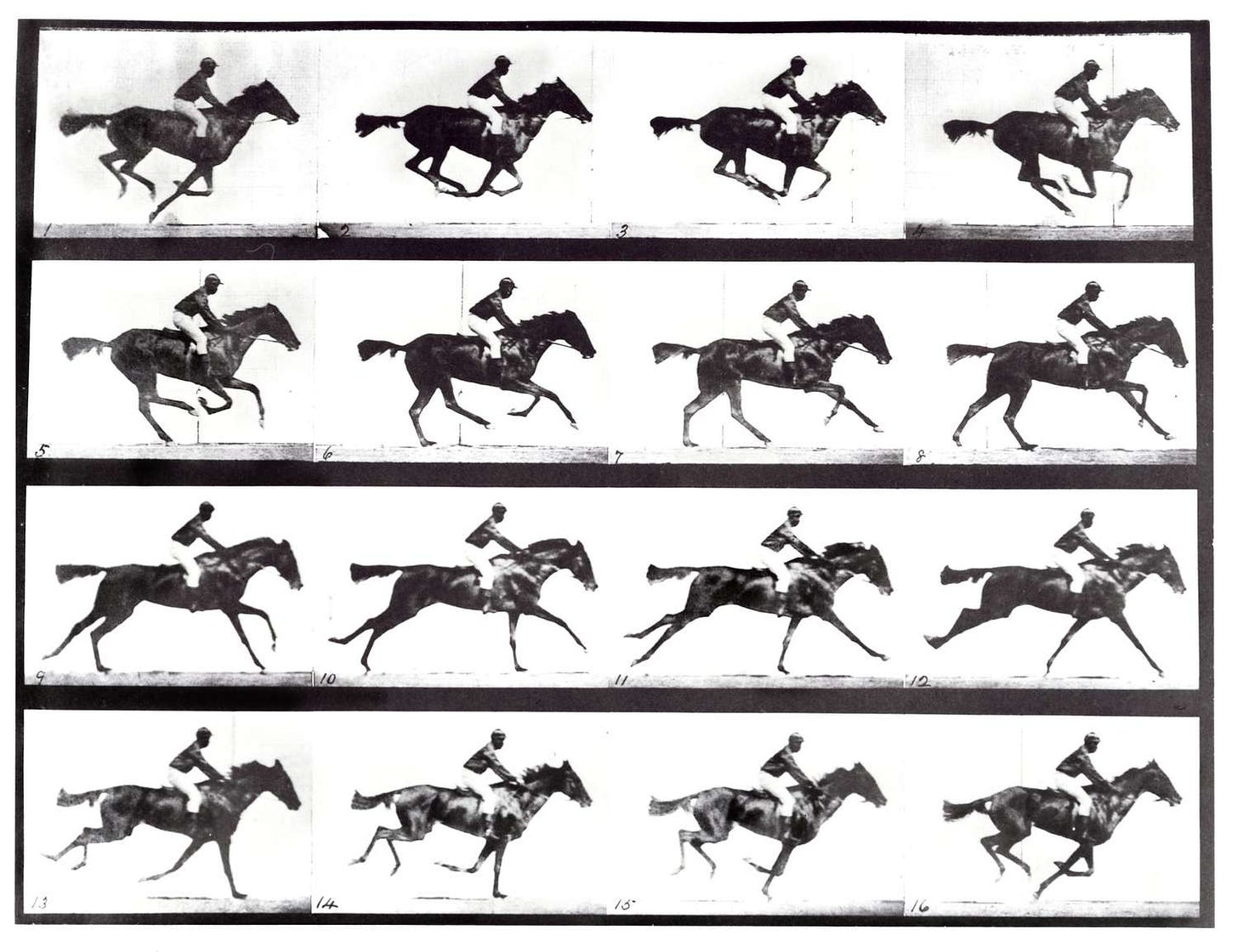

When you build a machine and set it in motion, will it run perpetually? Nothing can keep going forever. Energy can neither be create nor destroyed—the machine cannot produce more energy than it uses—and friction and other elements will eventually dissipate energy. Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music (mislabeled in the title sequence) puts this into sound:

We never get to the center of great art because, even if it cannot endure infinitely, its meanings and possibilities are too varied and extensive for us to comprehend—we just don’t live long enough to have the time to live with it long enough to fully understand it. We can marvel at those infinities.

Steve Reich’s greatest works are not about his technical and formal ideas—which are historically important—but how they pace and describe the infinite creation of time. He gets at something that is deeper than Philip Glass’ renewal and repurposing of counterpoint and voice leading, Terry Riley’s dervish repetitions, La Monte Young’s spiritual drones, Arvo Pärt’s profound mysticism, even Meredith Monk’s embodied musical practice; Reich shows you the universe and time expanding through sound.

Reich, who turns 89 today, likely understands more about how motion works (intuitively if not consciously) and the laws of thermodynamics than any living artist, because his process music describes what time is doing. Time, of course, is integral to the existence of the universe, and may be a product of expanding space. Infinity, if it is real, comes from space itself which may endlessly expand even as the universe, in several trillion years, subsides into thermodynamic equilibrium, or heat death.

I am interested in perceptible processes. I want to be able to hear the process happening throughout the sounding music.

Okay, deep breath. Even with the real cosmological implications (did you ever think of Reich as making space music?) this is still music, which we hear and feel and follow through time. The sound and experience of this is as gripping and satisfying as there is. It has a clarity of means and purpose that is like the most compelling prose, and because his compositional aesthetic is that music is a gradual process, hearing that unfold is immensely attractive to the ear and mind.

Reich is one of the great composers in Western classical history. It’s easy to toss around that word and it is also an honest description of both his stature and the experience of his music. Those are markers, not metrics, and measuring what he’s marking is a way to see what is often so difficult, which is the nature and, really, the size of greatness when it is living right in front of you.

The pieces like Drumming, Music for 18 Musicians, Different Trains, The Desert Music, Proverb, and many more are full of the glories of music, the sonic and physical pleasures, the force of ideas, the thrill of how it defines and fills time. He and Glass opened up a new direction in classical music in an era when the institutions of composition were driving what they imagined to be the future into a dead end. The concept and style they established is now an essential tool available to composers. There have been many great musicians who’ve made great music, far fewer who have added new vocabulary, syntax, and grammar to the language: “What I’m interested in is a compositional process and a sounding music that are one and the same thing.”

Performing and listening to a gradual musical process resembles…placing your feet in the sand by the ocean’s edge and watching, feeling, and listening to the waves gradually bury them.

There’s more, and language is the key. Like the greatest artists, Reich not only established his own language but developed it through time. He’s an admirer of Stravinsky and Miles Davis, and like them he moved through several periods, changing the way he made music but also speaking in his own, recognizable voice.

The strength of minimalism shows through how two wildly different composers, Reich and Glass, can define it. Glass’ early avant-garde works, pushing repetition as far as possible to see where it might break, are more extreme than Reich’s, but when he got his answers he incorporated them into a style embedded in the classical tradition of counterpoint and voice leading. He’s been extending the mainstream of that tradition for decades with his operas, symphonies, and piano etudes.

Reich has stuck to not only his process but the idea of process, channeling the ongoing flow of time—itself a process of gradual change on a universal scale. He sets it in motion and shows how time works through how it produces change. In a metaphysical sense this models existence itself. Reich’s music is artificial in the sense that it is something that is constructed out of symbolic language, but while played it connects us to the most fundamental feature of existence: time.

While this is something not many people hear, it’s something that we can’t help but feel, that tremendous forward pull in all his work, even the few things without pulse, like Traveler’s Prayer. It makes him one of the most fundamental musicians ever, and also still outside the mainstream of the classical tradition (and many other Western traditions). Unlike Glass who can write a modulation as elegant and profound as Bruckner, when Reich wants to change a key, he just goes to it, without preparation (this after he spent eight years never changing keys).

Musical processes can give one a direct contact with the impersonal and also a kind of complete control, and one doesn’t always think of the impersonal and complete control as going together.

Hearing this happen in front of us and in something close to real time is a profound and unique experience. For decades, we’ve been able to hear new things in the concert hall and on record, and there’s a palpable contemporaneity to it, music that is happening in and from the recognizable world. Think of how his pieces show how they are being constructed as they move along, like a time lapse video of a building going up. Even without his unassuming, direct harmonic and melodic ideas, the syncopations, there is the deep satisfaction of tension and release coming not through dissonance-consonance resolution, or setting up and reaching a final point, but through hearing how something is being made. That’s so honest.

This is essential to his appeal to audiences outside of classical music. He has always been public facing and was so in a time when a cultish obscurantism was the dominating aesthetic. He makes a moving statement in “Music as a Gradual Process,” that:

The use of hidden structural devices in music never appealed to me. Even when all the cards are on the table and everyone hears what is gradually happening in a musical process, there are still enough mysteries to satisfy all. These mysteries are the impersonal, unattended, psycho-acoustic by-products of the intended process. These might include sub-melodies heard within repeated melodic patterns, stereophonic effects due to listener location, slight irregularities in performance, harmonics, difference tones, etc.

While performing and listening to gradual musical processes one can participate in a particular liberating and impersonal kind of ritual. Focusing in on the musical process makes possible that shift of attention away from he and she and you and me outwards towards it.

Celebrate it, there’s no way to know when another movement of this consequence will come along again. And there’s no way to know, or even expect, what might be left to come from this generation that invented minimalism and gave it to us to learn. It’s not just the special kind of historical moment when a group of musicians can create their own path against the consensus, but that they pioneered this music as public artists. They drove cabs and hauled furniture and shared ensembles and went out into the public to communicate with the public. That way of being a composer in public and outside both academic and pop worlds, being avant-garde and experimental in public and risking failure, or at least incomprehension, just doesn’t exist anymore at any kind of scale. It has been engineered away by the consensus of American political economy.

We’re at the point in history where we not only have lost that possibility, but we’re going to rapidly lose the actual remnants of that past. The artists who created minimalism are not going to be with us much longer. Terry Riley and Arvo Pärt reached 90 this year. Even though La Monte Young belongs outside minimalism, his friendship with Riley is important to the social conditions in which the music came about, and he turns 90 on October 14. Next January 31 is Philip Glass’ 89th birthday, and Meredith Monk is only a few years younger—November 20 is her 83rd birthday. No one lives forever, nothing runs forever, except the universe itself. Reich gives it sound, as it goes, going on.

YES. I've never read anything that explains so eloquently why Reich's music is important/essential/enduring.