Bruckner at 200

Anton Bruckner has a unique status in the mainstream classical repertoire in that there are no casual Bruckner listeners. He gets either positive or negative attention, but never indifference: no one goes to a Bruckner performance just for the hell of it, WQXR never plays a single movement or even a full symphony during their day and evening programming blocks, no one has a set of the symphonies in their home library just to own one. Bruckner, he’s either loved or loathed.

I'm writing this for his 200th birthday (September 4, 1824) because I love Bruckner. But that wasn't always the case, and it helps me understand why people loathe him. His symphonies are long (though no longer than Mahler's) and they have a structure and form that can frustrate listeners who enjoy classical ideas of symphonic development. There's a consensus that he has too simplistic, didn't know how to keep his ideas together, and even needed the help that many gave him in revising his scores (he is the unusual major artist who had so little confidence in his ability, and negated his own ego in his admiration of his peers, that he gladly went along with their short-sighted and clichéd criticism of his composing—this was not due to his artistry but his unusual personality, which was both extraordinarily devotional and naïve). I used to think all that.

And I was wrong. I had this revelation in graduate school, in an advanced musicianship class. We were doing dictation, and the teacher gave us the first bass note and the key, and then proceeded to play the most exquisite modulation I ever heard. It was so elegant it seemed simple, but it moved to such a distant key so easily it was like traveling to another universe in a single step. No one got it all, everyone had put down their pencils before the end. Someone asked what that was, and the teacher said it was the Adagio from Bruckner's Symphony No. 8.

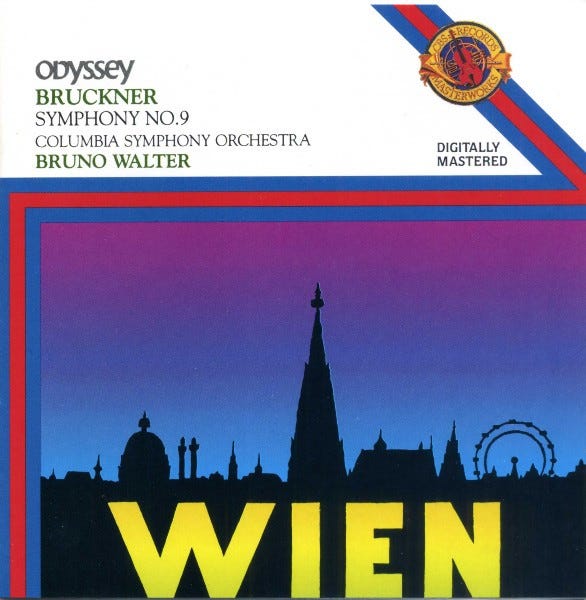

I realized the consensus was shaky, if not wrong, and went to the library to listen to Symphony No. 8 and, on the recommendation of a conducting student, Bruno Walter's classic recording of Symphony No. 9 for Columbia.

What that album shows is the two-fold greatness of Bruckner. The symphony is new music before it's time (structurally he can be heard as a direct precursor to Philip Glass, building large-scale forms through repetition and juxtaposition of discrete ideas, put a Bruckner Adagio against Part 1 of Philip Glass’s Music in 12 Parts and you’ll see what I mean), and one of the most profoundly mystical musical artists of all time. As Robert Craft recorded in Expositions and Developments, Stravinsky said that “I think that the Adagio of the Ninth Symphony must be accounted one of the most truly inspired of all works in symphonic form. Indeed, Mahler seems much less original than Bruckner, when one knows this music, and no composer of that period is so personal a harmonist as Bruckner.”

That personal foundation was Bruckner’s devotion, which was deep. Though his symphonies’ effects, you can feel the physical sensations of the possible transformation and immortality of the soul, the glorification of God, and the equally true and honest and essential terror before such incomprehensible presence and power. Bruckner is the sound of both the heavens and the abyss, which is not a void but the infinity of belief and of God’s universe, an understanding that Catholic faith isn't just a set of rules and believing in something that can’t be seen, but giving oneself over to something beyond understanding, something that if you did understand it would drive you insane or into a profound mystical practice. That is the terror and exaltation of the "Apocalyptic" Eighth Symphony.

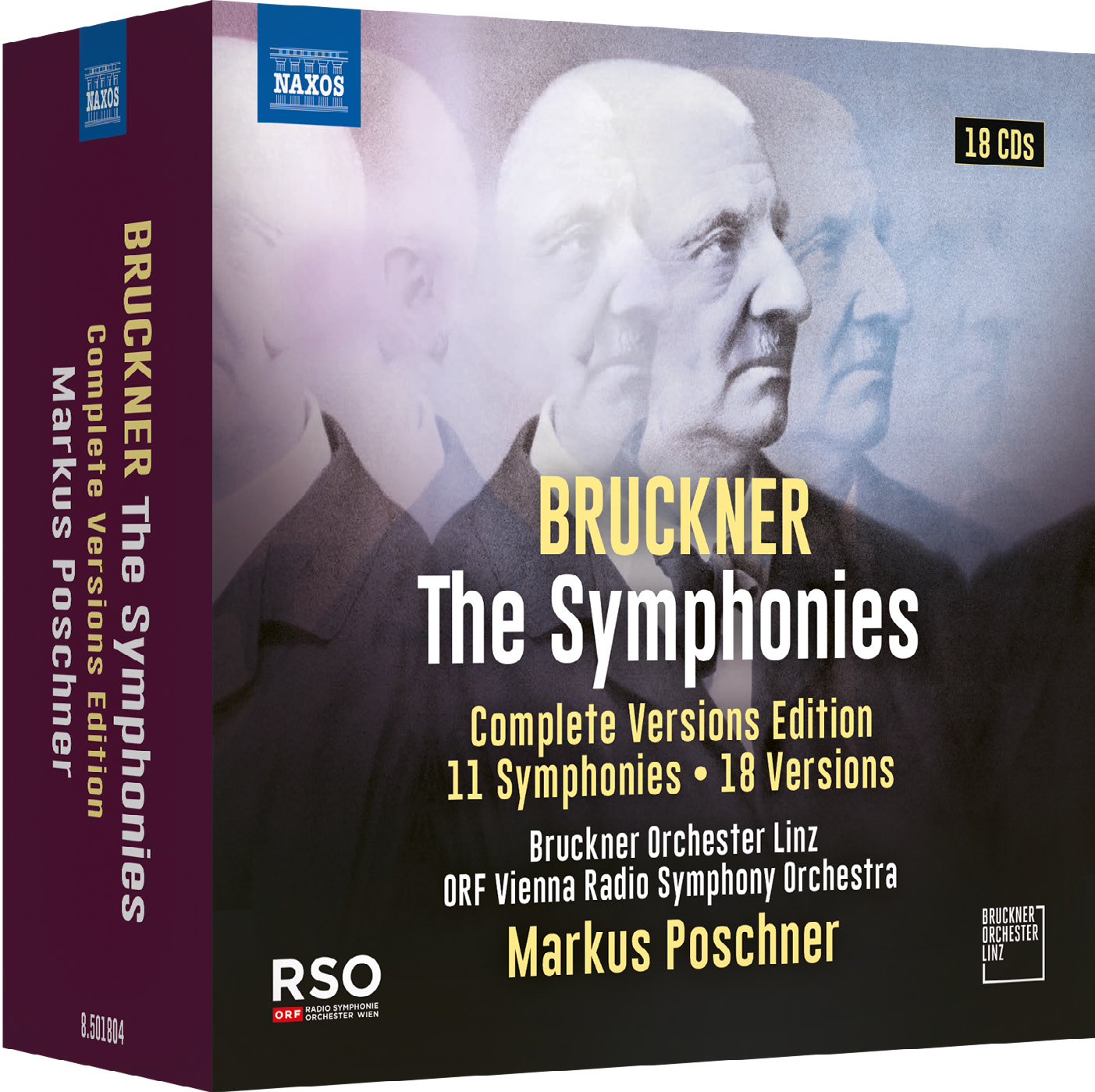

For those of us who are Bruckner lovers, and for those who are willing to love him, comes Markus Poscher's new complete set of Bruckner symphonies. This is more than a cycle of Symphonies 1-9, or even an expanded one with the “Student” Symphony in F and the “Die Nulte,” which is a complete but abortive sketch. This is Bruckner’s full, finished symphonic thoughts, with the existing multiple editions of each of the symphonies for which there is more than one existing performing (and performed) version: 11 symphonies on 18 CDs with multiple versions of Nos. 1-3, 4, and 8. There’s also a 174 page booklet with extensive musicological notes by Paul Hawkshaw.

Along with the various versions, these symphonies have had many editors through the centuries. The editions recorded here are edited by Nowak, Carragen, Korstvedt, Hawkshaw, and a few others.

And in point of fact, and the Bruckner community being what it is, this set is not 100% complete in every detail! As noted at abruckner.com (John Berky’s home for the Bruckner discography and archive), there is one alternate movement published in the New Bruckner Edition of scores that Poschner did not record, the "Alternate Adagio" from 1887-1889 to Symphony No. 8—the printed parts were simply not yet available during the recording sessions. Berky is completing this himself for anyone who orders a copy of the new set through him by providing a separate CDR with

The Overture in G Minor (1863 version)

The Overture in G Minor (1862 version)

The "Alternate Adagio" from the Symphony No. 8 (Gault/Kawasaki edition)

The Symphonic Prelude (attributed to Bruckner)

The Four Orchestral Pieces

The March in E Flat Major

As he points out, with the CDR, “the set is not only a complete set of symphonies but a set of Bruckner's COMPLETE ORCHESTRA MUSIC!” He will be selling the set for $79.95, plus postage, which is a substantial discount from the current prices at ImportCDs, Amazon, and Presto. To reserve a copy, email him at john@abruckner.com.

Listening to Bruckner

…The possibilities of frozen time in the music, or the expansion from mere, though wonderful, musical structures into transformative experiences.

With that discographical detail covered, what is this set like as a listening experience? To get to that, it’s worth returning to the identity of the Bruckner listener, who again is not casually interested in the music—and there’s nothing casual about this collection which is as much, if not more, a musicological as musical listening experience. That this even exists is a great value for Bruckner lovers. But despite its comprehensiveness, it is neither the full nor last word, it sits in between the Georg Tinter cycle of the first versions of the symphonies and whatever your favorite set of whatever you feel is the best versions of the works.

That is a matter of individual taste, and for what it’s worth after living with and eventually selling off my sets conducted by Jochum (both), Barenboim (three), Simone Young, Volkmar Andrea, Marek Janowski, Dennis Russell Davies, Heinz Roegner, Fürtwangler, and Haitink, I have kept Tintner, Karajan, Stanislaw Skrowaczeski, Günter Wand’s cycle with the Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester and the incomplete sets from Celibadache live, Bruno Walter, and Wand again in live recordings with the Berliner Philharmoniker. Although those last three between them lack Symphonies 00-2, they are the ones I care about most deeply, they have the greatest power, the most profound beauty and spiritual and humane understanding of the music. Celibadache, with his unique slow tempos, is not for everyone, but the Bruno Walter set is something every classical music fan should have as the box is his Columbia Bruckner and Mahler recordings, so both authoritative and personally connected to the composers, while Wand live is simply the greatest, with incredible playing from the orchestra and an almost frightening level of power in both the light and the darkness (both are still in print, though seem to be disappearing, and at very reasonable prices).

The performances of the early symphonies, up through No. 3, are solid (no one can rescue the “Die Nulte” so it doesn’t matter), with the curious feature that for symphonies with multiple versions, like the Second and Third, the performances of the earlier versions are a little perfunctory, while the latest version is well thought and played. Perfunctory is the single drawback to Poschner’s approach. The music making is mostly solid and without flaws, through not at rarified levels, but when things aren’t that good it’s because they feel a little flat, they don’t quite breath, the pace may not be rushed but it feels like it’s just marking the passing measures.

That can be the case with complete performances, like those of the 1876 and 1878-1880 versions of Symphony No. 4 (the disc for the latter has the “Volkfest” finale tacked on as a fifth track), or else stretches of otherwise fine renditions. Bruckner made only one version of the sophisticated and transitional Symphony No. 5, and the first three movements here are clear, cogent, and committed. But the finale is a let-down, without the same depth as the previous music. There are similar passages in the finale of Symphony No. 6, which is otherwise a very fine performance, where there’s a sense of impatience in the playing. There are also stretches of the first movement of Symphony No. 7 that suffer from the same lack what I would call an appreciation for the possibilities of frozen time in the music, or the expansion from mere, though wonderful, musical structures into transformative experiences.

But the great value in this cycle comes through in the two performances of Symphony No. 8. This is a great masterpiece and arguably (with the Ninth) the single greatest example of Bruckner’s art. The 1887 and 1890 versions (and the Ninth) are played by the Bruckner Orchester Linz, and they are mighty fine, with terrific pace and a sense of gusto. Together, they convince me that while the 1887 version is good, the 1890 one is vastly superior, the real masterpiece because, despite its duration, it expresses itself clearly and cogently every moment, nothing is wasted.

The Man Outside Time

The alpha and omega raison d’être for this set, though, is as a wholistic presentation of Bruckner’s art. His music expresses his personality as deeply and plainly as Mahler’s does his own, Bruckner is just a vastly different person than Mahler and than you or are I likely to know in our lives. The combination of absolute certainty and serenity of his faith with the negation of ego that produced, and insecurity in his own work, we are simply not accustomed to in the public expressions of artists in any medium. And by unique, I mean that this kind of insecurity in our modern, global society stifles artistic production and presentation. We don’t know about such artists because their work never comes to fruition. Bruckner’s personality is what today we identify as that of the outsider artist (and he was self-taught until early middle age), yet his craft is learned and polished and embedded in the tradition of Western art music. It is his vision and sensibility that stand as utterly strange vis-a-vis our own society, including those who profess faith but are enraptured by materialism, consumerism, capitalism, and especially an authoritarian politics that seeks to segregate peoples into those who deserve to live and those who can be thoughtlessly discarded.

Bruckner is more than mere notes. His symphonies are the greatest expression of Catholic faith in music, the word and the ego-dissolving incomprehensibility. He was not just a great harmonist and contrapunatlist but a great organist and improviser. He plaid for a decade at Sankt Florian Cathedral, and that is his musical architecture, composing that built formal shapes that sound and feel like an enormous Gothic cathedral, with vaulted arches raised high and which, in their candlelit chiaroscuro, held the mysteries of the meaning of existence and of the soul. In the booklet, Norbert Trawöger, artistic director of the Bruckner Orchester Linz, writes the that he “burst out of the confines of the cathedral using that most secular of musical forms: the symphony. Here is a man whose music engages, us and God in conversation. Pious old Bruckner, it turns out, was also a heretic. As are all mystics.”

We have a socially conditioned idea of what mystics are supposed to be like, and Bruckner’s country-bumpkin/petit bourgeois presentation subverts that (Scelsi was a cousin in this, and not far different musically). As does his method: he’s not a storyteller, he’s not about sculpting the satisfactions of abstract harmonic structures and getting to the home key, he’s about the fundamental questions or who am I, and why am I here, and knowing in the fiber of one’s being that death is the necessary transformation of life. And there’s no casual listening to that.

Good listening to all.