Satori of Small Moments

What is time but a constant series of transitions from past to future? There is a “now” that seems notional. Each letter I type on this screen, once it has appeared and seen by you, is in the past, and each that follows is a further step into forming and completing words and thoughts in the future. The past is a matter of record, the future is gained in each passing moment, there’s no now to hang on to.

This flashed in my mind a week ago when I played the stunning new album from The Necks, Disquiet (Northern Spy Records, October 12). It takes time; the shortest track is 26:06, the two longest (of four total) are 57:07 and 74:00.

My feeling is it could be longer. The Necks are an enormous topic of their own, and if you’re not familiar with them they are an extraordinary improvising trio that sits in between jazz and new music and has a singular style that makes quiet, delicacy, focus, and deliberateness into exalted qualities. This is an enthralling and tectonically beautiful album that will not be surpassed by anything else this year.

Apologies for the gap between posts—since I announced my push to add paid subscribers, I’ve see one come aboard and one depart, for a net ZERO! So there’s been a struggle between discouragement and motivation. For reasons to subscribe and a giveaway offer good into Labor Day, see this post. And thank you.

How Soon is Now

And it unfolds, slowly, which is a particular and great pleasure for me. All music unfolds in time—it exists in no other dimension—and so exists on a truly transitional plane. Musical structure and form exist because we can remember the past and anticipate the future. Music that unfolds slowly uses time to maximum effect, a measured pace deepens memory and heightens anticipation. It’s not a style but an idea, it works in Sibelius’ Symphony No. 7 and in the Moroder/Bellotte/Summer synth-disco “I Feel Love.”

Back to the now, and whatever the hell it is. St. Augustine wrestled with this experience, and how to describe it. Reading his Confessions, years ago, was a first step for me in being able to articulate something that was bedeviling, that philosophical, experiential, and physical step through all these transitions, being aware that there’s no real now and not letting that drive me insane. Not that it should, because humanity could not have survived and evolved if it was driven mad by one of the integrated dimensions of existence. But as someone who makes music, thinks about music, and writes about music, time has become an increasingly acute and critical part of my experience.

Time, and my thoughts about it, give me the pleasure of the slow unfold, and are what motivated me to write my book on minimalist music (you can preorder it). Time is the fundamental criteria in the book, as I explore how minimalist music works with and articulates time in ways that define it, and separate out the “minimal” from the “minimalist.” By that I mean there is music that hops aboard passing time as if it were a horse and makes the most out of what the animal can do, that is carried by time and shows that working. It is process music, and the process is fundamentally time.

Going My Way?

This is experiential and physical, it is the sound of time passing and also how time might actually, literally work, as a product of particles and their speed and vectors in space, i.e. that as the universe expands, each new instance of space created adds another moment of time.1 Repetition articulates this, but not just any kind. Most music has repetition, things like pop songs and Haydn symphonies use repetition to build chunks of musical form within the universal flow of time, though outside of the experience of it. Listening to that music puts you in a musical time that is outside physical time.

Drone music also builds musical experience outside of time, often for psychological and spiritual purposes meant to work outside of physical time. That is the dividing line I work with, and why I can’t include La Monte Young in the story of minimalism.

His Trio for Strings is important, it jolted Terry Riley out of the conventions of serialism and made him realize that music could be something not only different than what he expected but more like what he wanted. What Trio for Strings did was violently bust apart the music composers were supposed to be making in 1958. What’s lost to history is that Young’s original version used atonal harmonic procedures, played in slow, quiet, extended pitches with long pauses in between, taking several hours. Young finished dismantling serialism as he moved to just intonation, and that’s the contemporary version of Trio for Strings.

But it’s not minimalism, it doesn’t repeat anything that can be followed in memory except for the gestures of long tones, long silences, then again. It doesn’t work with time and it’s not meant to, it’s for bringing together people in a shamanic experience outside of time. And it absolutely works that way, lying on the floor of the Dream House, in silence with other people, then leaving in silence. What is odd, though, and even disappointing is that this historic recording doesn’t work at all at home. The social, community aspect is missing, and this isn’t music you sit and listen to, it’s ritual music. I say this from first hand experience—and this is why live music is invaluable to criticism—I was at this performance that was recorded, and the album can’t even remind me of it. My memory is stronger without the music.

Baba O’Riley

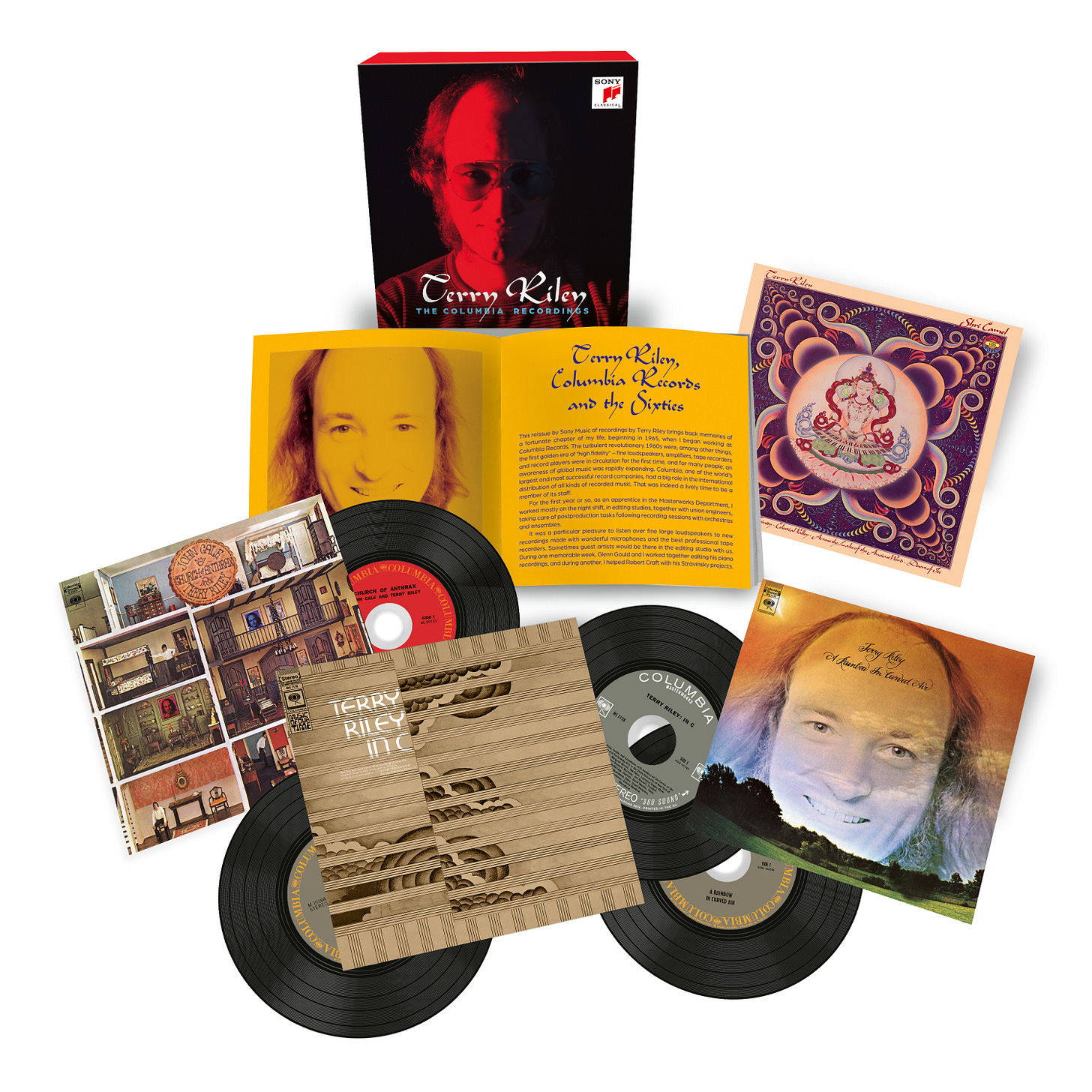

The greatness of the wonderful Terry Riley is that once Young showed him you could make music that could sit there in time, he made the first minimalist piece, In C, which articulates time through repetition to build something glorious (with some help from Steve Reich, who suggested the ostinato pulse and played in the premiere performance, along with Pauline Oliveros and Morton Subotnick). Riley saw that as the first step in his own path to build a shamanic practice, and then used mantra-like repetition, with his own virtuosity, to get there. The Keyboard Studies, Rainbow in Curved Air, and the like are entrancing. They hold time in place while articulating the segments that would otherwise be passing—the music transforms the sense of being in time.

There isn’t much like it. Riley turned 90 this year, and Sony has put together the four albums he made with Columbia for what is a snug set that belongs in any contemporary music collection. Riley is truly a rare figure, and a very American artist. His music making extends from the Great American Songbook to the avant-garde, like Charles Ives and Sun Ra, and like them he’s made American musical culture essential to the planet. Along with the Columbia albums, Eighty Trips Around the Sun: Music by and for Terry Riley would give you a substantial and meaningful Riley discography.

This release bookends the above box, with a couple pre-In C atonal pieces and then later piano works, along with tributes from prominent colleagues. And the great advantage these two sets have is that they are available—Riley is the kind of misfit musician who has an important discography that goes in and out of print. Descending Moonshine Dervishes and Persian Surgery Dervishes are the best examples of who he is, but you’ll have to find them in the aftermarket or hope that someone else licenses them for a limited run (the Beacon Sound reissue of the former sold out almost immediately). Riley doesn’t just have fans of his music, he has devotees to his shamanic practice, which is an unshakeable connection. Dig in to these, he will sanctify you with time.

Good listening to all.

Suggested further reading:

Time: A Very Short Introduction by Jennan Ismael

Now: The Physics of Time by Richard A. Muller

From Eternity to Here by Sean Carroll

The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli

Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe by Lee Smolin

A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

Time: The Familiar Stranger by J.T. Fraser

The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies by Jonathan D. Kramer

Beautiful essay. Been reading about The Necks for a long time, have never heard them. Thanks for turning me on to them.